So this last weekend (Labor Day weekend here in the States), I was faced with the final task. I had made custom moldings to go on the front of cabinet, much like a picture frame. But I needed to miter the corners and install the moldings. I've cut miters before, always with my power miter saw. And in all honesty it's an exercise in fear and frustration. With a miter saw blade spinning at something like 3,600 RPMs, there is a serious element of fear, even with proper wedging and clamping. And frustration is on the high side as well. I'm sure if I cut as many miters as professionals do, I would soon find it much more natural. But it's always a challenge to get that miter just the way it needs to be, especially if you are matching one you cut that is not quite 45 degrees.

So, I took the plunge and made a shooting board. I've read many articles about shooting boards, and they appeal greatly to my continued foray into hand woodworking. I was encouraged by the description of the precision you can achieve with them. I wanted to reward all of Penny's help and patience (over the last year especially) with the very best I could build. So, after one more look over the articles, I settled on a design for a shooting board that would work for both right angles and miters.

Rather than write up a long description of shooting board design, I'll refer you to several resources I found very helpful:

- Finewoodworking.com - if you have a subscription, there quite a few articles and 'tips' regarding shooting boards. If you instead have a old issues of Fine Woodworking, the May/June 1994 magazine has a short article that inspired my removable 45 degree stop.

- There is a really good article on the Popular Woodworking website.

- "The Handplane Book" - by Garrett Hack, a wonderful text on all things hand plane

- "Shooting Boards @ Cornish Workshop" - this is perhaps the most important link. Not only is it informative and filled with links to other online references, but Alf's no-nonsense write-up convinced me that "It's Not Rocket Science" and it was worth a brief 'diversion' to achieve better results for Penny's cabinet.

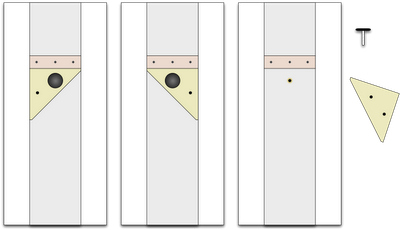

So I settled on a design, a blending of several different ones I've seen over the last few years. I chose to make a single board that has a shelf on both sides. While this means aligning the stop block at exactly 90 degrees is particularly important, it means only one shooting board in my shop for mitering on either the left or the right. And with a removable 45 degree block, I can orient for 45 degree miters on either side in less than a minute.

One of the surprising things I learned from Alf's shooting board pages was that most of the dimensions of a shooting board aren't all that important. The only key dimension is the size of the shelf on which your hand plane rests. It needs to be wide enough that you can apply good, firm pressure down and toward the cut without having your hand plane tip over.

I decided to go with the removable 45 miter block in order to build only one shooting board (at least until I want to do "dog-ear" miters). That proved to be tremendously helpful when it came time to fit my trim on Penny's cabinet. My angles weren't quite 45 degrees and I simply added a piece of paper or card stock to one end or the other of my angle block to finesse the angle into what I needed. Because I have a threaded insert and a knob with threaded rod to lock the miter block in place, I can adjust the wedge to where I need it and to as many cuts and test fittings as needed to get a good fit without worrying that my shooting board setup will change.

Since I was going to use a shooting board, I decided it was time to try out the hand miter saw I got several months ago. It's not in perfect shape. It has some rust that needs removing on the box and saw guide, and the paint is flaking and needs to be scraped and repainted. Plus the saw itself (a nice large example with a 26" length) was rusty enough that I left rust marks on the scraps I used for test cuts. So I took some time to clean the blade, clean the gunk from the corners where the bed and fence meet, and experimented until I was comfortable that my cuts were close enough to 45 degrees for good results.

I still need to finish cleaning up the miter box but now that I've used it with success, that time will be much more pleasurable to spend.

Once I had completed the shooting board, it was time to actually cut the last two pieces of molding and make them fit the two I had already glued to the cabinet carcass. I will admit I "took a break" and went upstairs for a bit. After a suitable length of "rest" (also known as gathering my nerve), I went back down and set to work.

The first piece I cut was definitely too long by more than an 1/8th of an inch. But that turned out to be a good thing. While I had experimented with some scrap pieces, that's just not the same as taking custom made molding to a shooting board you've never used before. That extra length gave me time to learn the feel of my shooting board, and I learned a lot about reading the angles and the fit. I also realized immediately how much more I was enjoying the process with hand miter box and shooting board versus power miter saw. The finesse the shooting board gave me, the soft "shhnick" from taking a truly fine shaving by hand, the quiet of the workshop, and not having to pay huge attention to a saw blade spinning at 3,600 rpm made the process a joy instead of a test of will with a dash of fear.

So now Penny's display cabinet is finished, and I have a shooting board I will use to improve my results for years to come.

Once I get Penny's case installed, of course...